As we play, sing, and explore the precious collection of manuscripts from the Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine, in Kyiv—made available through the Kiselgof-Makonovetsky Digital Manuscript Project (KMDMP)—we can ask questions about the repertoire. What genres are represented? What is the balance of core Jewish, transitional, co-territorial, and cosmopolitan repertoires? How do the collections from different sources compare: the wedding book from Makonovetsky (b. 1872), a violinist who was an important informant for Beregovski; the notebook (Heft) from Motl Reyder, a violinist from Dubno (b. 1843); the repertoire from Moisei Komedian Gershkovitch (dates and location unknown), and so forth. Where does the repertoire come from? Mariko Mishiro has done important work on these questions based on Beregovski’s catalog of tunes (Mishiro 2021). Mishiro observes, for instance, that there is a large proportion of core repertoire, more than in the American recordings of Naftule Brandwein and Dave Tarras.

Here, I would like to dig a little deeper and ask questions about the tunes themselves, and especially their use of musical modes. What can we say about the klezmer modes based on this repertoire? How do the modes differ by genre or by informant? How do the modes in these manuscripts compare with those in Beregovski’s Jewish Instrumental Folk Music (2015) or in other collections and sources?

I will focus on a subset of the larger KMDMP collection: eighty-five tunes in a notebook from Motl Reyder. This is a manageable collection for initial study. It includes a set of skotshnes and freylekhs representing core repertoire; a collection of bulgars, oras, and anges representing transitional repertoire; a few mazurkas representing cosmopolitan repertoire; and other miscellaneous items. The combination of core Jewish, transitional, and cosmopolitan repertoires is striking; it is “between two worlds” as I suggest in the title of this essay.

In thinking about modes in this repertoire, I am thinking not only about pitch collections and central pitches or “tonics,” which can be represented in scales. I am thinking also about characteristic melodic figures, chromatic alterations, cadences, and modulation pathways—i.e., moves between related modes. (Harold Powers outlines this broader definition in a classic article; see Powers et al. 2001, I.3.) The modes thus include things that klezmer musicians know intuitively from experience, the patterns that are part of muscle memory because they occur throughout the repertoire. And exploring the modes is important for understanding the melodic language of klezmer music and Ashkenazic expressive culture more broadly.

I will assume a basic understanding of four modes: (1) freygish or ahava rabboh, (2) misheberakh or altered Dorian, also referred to in some sources as the raised fourth mode, (3) minor or mogen ovos, and (4) major or adonoy molokh. The minor and major modes at times overlap with those of Western European tonality and at times differ, reflecting more of the modal characteristics of traditional nusach and cantorial repertoire. 1

Overview of Modes and Genres in Motl Reyder’s Notebook #

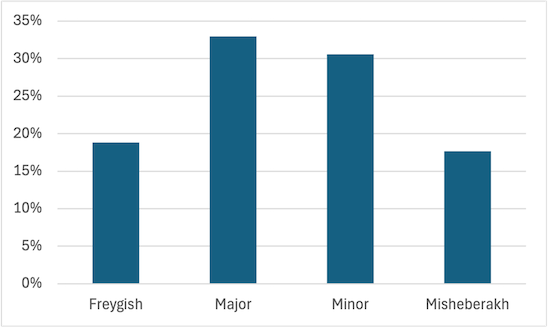

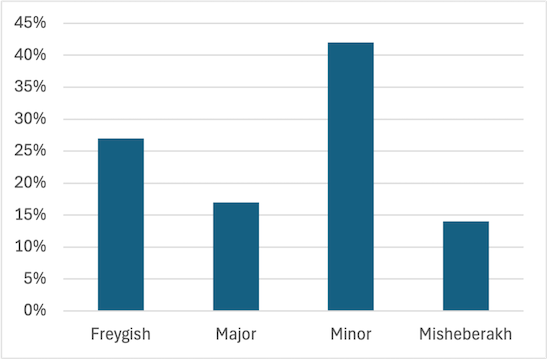

Example 1 below shows the number of tunes in each mode in the collection. The graph is based on a single modal designation for each tune; I will explore modal shifts within tunes below. Example 1 shows that all four modes are present in substantial numbers, but the major (adonoy molokh) and minor (mogen avos) modes are more prevalent. We are familiar with minor being a common mode in klezmer music, but it may be surprising to find that major is the most common mode in this collection. Example 2 provides the equivalent data from Beregovski’s instrumental volume; there minor is by far the most common with freygish a distant second and misheberakh and major least common.

Example 1. Modes in Motl Reyder’s Notebook

Example 2. Modes in Beregovski’s Jewish Instrumental Folk Music

There are a variety of explanations that one might offer for these differences. (1) It may have to do with the provenance of the tunes. Christina Crowder and Joshua Horowitz both observed to me that many of the tunes in Motl Reyder’s notebook feel Moldavian or Romanian (from the historical region of Bessarabia). Motl Reyder himself lived in Dubno, Ukraine, but tunes traveled widely; there is a great deal of overlap and no strict boundaries. (2) The differences may have to do with the genres represented (which also relates to geographic trends). Most of the major-mode tunes in Motl Reyder’s notebook are in transitional and cosmopolitan repertoires, and especially in the bulgars, oras, and mazurkas. In comparison, Beregovski has fewer bulgars (labeled bulgar or bolgarish) and no oras or mazurkas. (There are several zhoks that are analogous to oras or horas; see the discussion in Feldman 2016, 218–19.) (3) It may have to do with the individual musical tastes of Motl Reyder and Moisei Beregovski, or with Beregovski’s need to create a distinct but not too distinct representation of Jewish music in the Soviet context of the 1930s and 40s. All of these explanations are hypotheses, to be explored further with musical and contextual information. But the corpus-level data, exploring properties of these tune collections, begins to paint a picture of distinct trends.

We can explore the correlation of mode and genre more deeply with the table in Example 3. We may note, for instance, that there are sixteen Bulgars in the notebook, and ten of these are in the major mode. Or we may note that there are twenty-eight tunes in major and the majority (twenty-one) of these are Bulgars, Mazurkas, and Oras/Zhoks.

Example 3. Mode and Genre Correlations in Motl Reyder’s Notebook

I created a Motl Reyder Mode Analysis Table to show more detailed, tune-by-tune analyses. These analyses are also being saved and organized as musicological data for the Klezmer Archive Project. Christina Crowder provided images of the scores and manuscripts and links to recordings. The table includes the genre as shown on the manuscripts under “E working title” and a genre category for analysis and discussion here under “Yonatan genre.” The genre category allows me to group the “An’Ore” no. 980 together with the rest of the Oras, or the “Freylekhs (Skotshne)” no. 1014 together with the rest of the Skotshnes. The spreadsheet can be filtered by one or more columns. For instance, we can find all the tunes in major by clicking on the “E primary mode” button at the top and choosing Major. We can then find the major tunes that are also bulgars by clicking on the “Yonatan genre” button and choosing Bulgar. The spreadsheet provides further information about form, mode, and modal pathway for each tune. Daniel Shanahan and I have created an analogous spreadsheet for Beregovski’s instrumental volume; see the “Mode Analysis” page on the “Modes in Klezmer” website.

Modal Pathways #

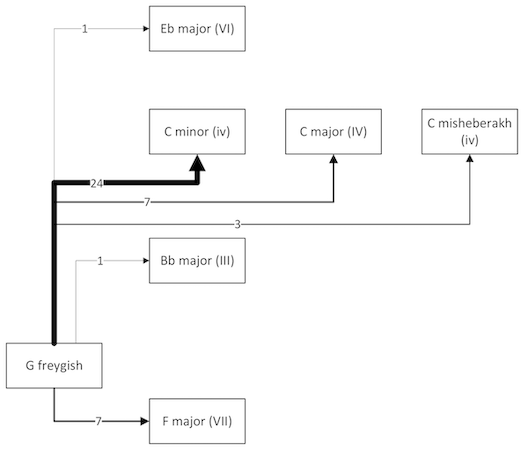

Klezmer tunes sometimes stay in a single mode throughout. And sometimes they “modulate” or shift to other related modes. When they do modulate, most tunes follow a set of common or characteristic pathways. For instance, freygish tunes often modulate to the minor mode a fourth up, e.g., G freygish to C minor. Freygish tunes may also modulate to the major mode a fourth up, e.g., G freygish to C major, or to a major mode a step down, e.g., G freygish to F major. Example 4 shows modulation pathways in Beregovski’s instrumental volume, for the tunes in the freygish mode. Beregovski notated all his tunes in G, so the network shows modulations from G freygish. Darker lines represent more common moves, and the numbers indicate how many tunes follow the given pathway. This diagram shows only the first modulation, other modulations may follow.

Example 4. Modulation Pathways from Freygish in Beregovski’s Instrumental Volume (first modulation)

Individual tunes following each pathway can be found on the Mode Analysis page from the “Modes in Klezmer” website. Thus, if we enter “G freygish” in the box under the mode column and “F major” (with quotation marks) in the box under modulation_pathway, we find all the tunes that include F major as a secondary mode. The Freylekhs no. 87 is a classic example; it can be heard in a recording by Abe Schwartz’s Orchestra on Columbia records, circa 1918. Listen for the shift to F major is section B, at 0:19 on the recording. 2

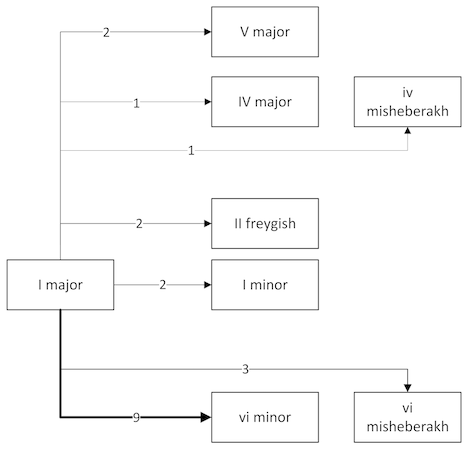

What about the modulations in Motl Reyder’s notebook? Many of them follow the same pathways. Example 5 shows the modulations from the freygish mode in Motl Reyder’s tunes. In this case, the tunes are notated with a variety of pitch centers (not only in G), so I show the pathways with Roman numerals and mode names. It is a more limited set; there are only ten freygish tunes that modulate in Motl Reyder’s notebook. But once again, the move to iv minor is most common. Tunes with particular pathways can be found on the Motl Reyder Mode Analysis Table: filter first by mode and then by Mode pathway. The Skotshne no.1043 (KMDMP 02-37-1043) follows the path I freygish to VII major—the same path as in Beregovski’s Freylekhs no. 87 mentioned above.

Example 5. Modulation Pathways from Freygish in Motl Reyder’s Notebook (first modulation)

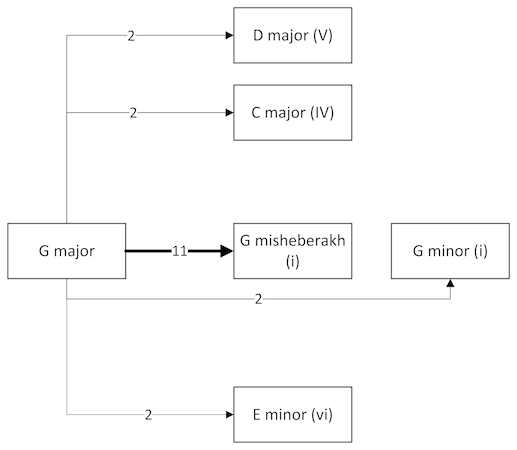

The most significant differences are once again in the tunes in major, primarily in the transitional and cosmopolitan repertoire. It is not only that there are more of these in Motl Reyder’s notebook; they also follow different modulation pathways. Whereas Beregovski’s tunes in major go most frequently to misheberakh on the same tonic (G major to G misheberakh), Motl Reyder’s major-mode tunes go most frequently to minor or misheberakh on the sixth scale degree (e.g., G major to E minor or G major to E misheberakh). Examples 6 and 7 compare the modal pathways for major-mode tunes in the two collections.

Example 6. Modulation Pathways from Major in Beregovski’s Instrumental Volume (first modulation)

Example 7. Modulation Pathways from Major in Motl Reyder’s Notebook (first modulation)

The modulation pathways contribute to the cosmopolitan feel of Motl Reyder’s repertoire, together with its more typically Jewish elements. Of course, the cosmopolitan and transitional tunes feel different for other reasons as well. Many of them are “tonal” in a Western European sense; the melodies are structured around motion from tonic to dominant and back. Christina Crowder observed that Motl Reyder’s Bulgars are reminiscent of military brass band music (personal communication). We don’t know anything more about Motl Reyder’s biography, but many klezmers in the nineteenth century played in military bands and fire-brigade orchestras (Feldman 2016, 113–114; Rubin 2020, 32–33).

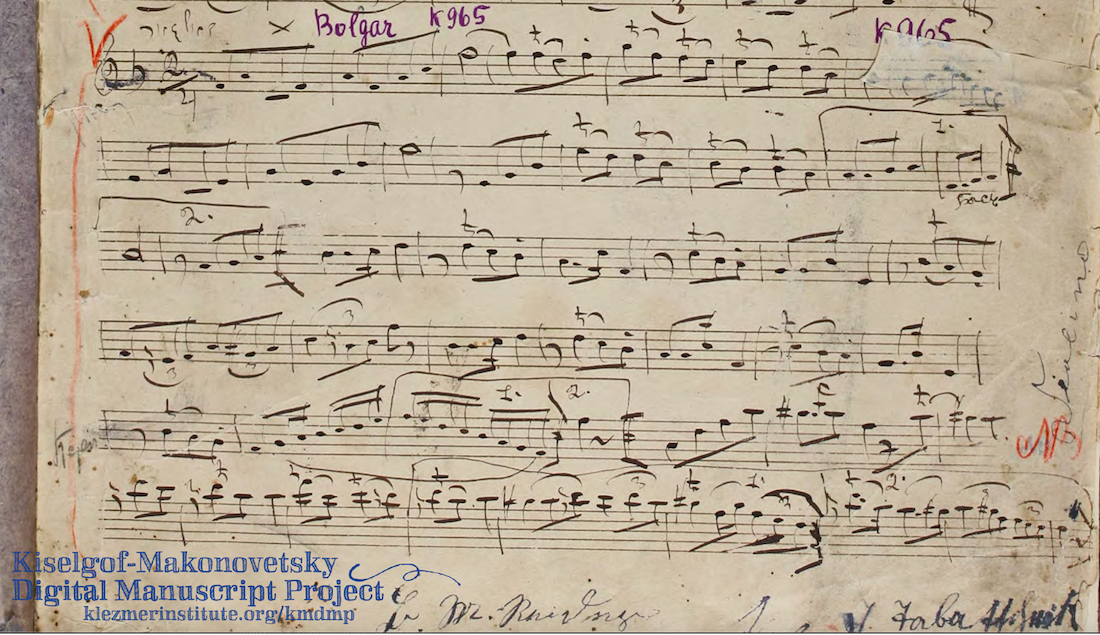

In thinking about the association with military bands, Christina cited the Bulgar no. 965 (KMDMP 02-37-965) with a recording by Suzi Evans and Szilvia Csaranko. Examples 8 and 9 provide the manuscript and score digitized by Mauricio Sanchez Rivera. The melody of the first section implies a broad F-C-F or I-V-I (tonic-dominant-tonic) motion. The third section moves to D misheberakh, or vi misheberakh, which suddenly feels more Jewish.

Example 8. Manuscript Page, Bulgar, KMDMP 02-37-965

Example 9. Bulgar, KMDMP 02-37-965 digitized by Mauricio Sanchez Rivera

This Bulgar and the entirety of Motl Reyder’s notebook document a meeting of worlds in the changing Ashkenazi culture of the time. Motl Reyder was seventy years old in 1913, when he passed the notebook on to Susman Kiselgof. He witnessed the evolving Ashkenazi culture through his life, performed it in his music, and documented it in his notebook of tunes that we are so lucky now to explore and enjoy.

References #

Beregovski, Moshe. 2015. Jewish Instrumental Folk Music: The Collections and Writings of Moshe Beregovski. Edited by Mark Slobin, Michael Alpert, and Robert Rothstein. Second edition, Revised by Kurt Björling. Draft 3.4.

Feldman, Walter Zev. Klezmer: Music, History, and Memory. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Horowitz, Joshua. 1993. “The Klezmer Freygish Shteyger: Mode, Sub-Mode and Modal Progression.” Unpublished manuscript. http://www.budowitz.com/Budowitz/Essays.html.

Malin, Yonatan and Daniel Shanahan. Forthcoming. “Modes in Klezmer Music: A Corpus Study Based on Beregovski’s Jewish Instrumental Folk.” Music Theory Online 31, no. 3.

Mishiro, Mariko. 2021. “Jewish Folk Music of the Early 20th Century in Ukraine as Seen in Zusman Kiselgof’s Manuscripts: Focusing on Klezmer Music.” KMDMP Anniversary Digitizathon (online). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-0QSj9xdtbc.

Netsky, Hankus. 2015. Klezmer: Music and Community in Twentieth-Century Jewish Philadelphia. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Rubin, Joel. 2001. “The Art of the Klezmer: Improvisation and Ornamentation in the Commercial Recordings of New York Clarinetists Naftule Brandwein and Dave Tarras, 1922–1929.” City University, London.

———. 2020. New York Klezmer in the Early Twentieth Century: The Music of Naftule Brandwein and Dave Tarras. Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

Sapoznik, Henry, and Pete Sokolow, eds. 1987. The Compleat Klezmer. Cedarhust, N.Y: Tara Publications.

For more background information, see Sapoznik and Sokolow 1987, Horowitz 1993, Beregovski 2015, I-23 to I-28; Netsky 2015, 101–5; and Rubin 2020, 122–26. ↩︎

I will present the network diagram in Example 4 and others like it in an article co-authored with Daniel Shanahan, forthcoming in Music Theory Online (Malin and Shanahan forthcoming). Joshua Horowitz documented similar modal pathways in an article from 1993. And Joel Rubin provides a comprehensive catalog of the modulation pathways in recordings by Naftule Brandwein and Dave Tarras in his book New York Klezmer in the Early 20th Century (2020) and his dissertation (2001). ↩︎