Manuscript to Encoding #

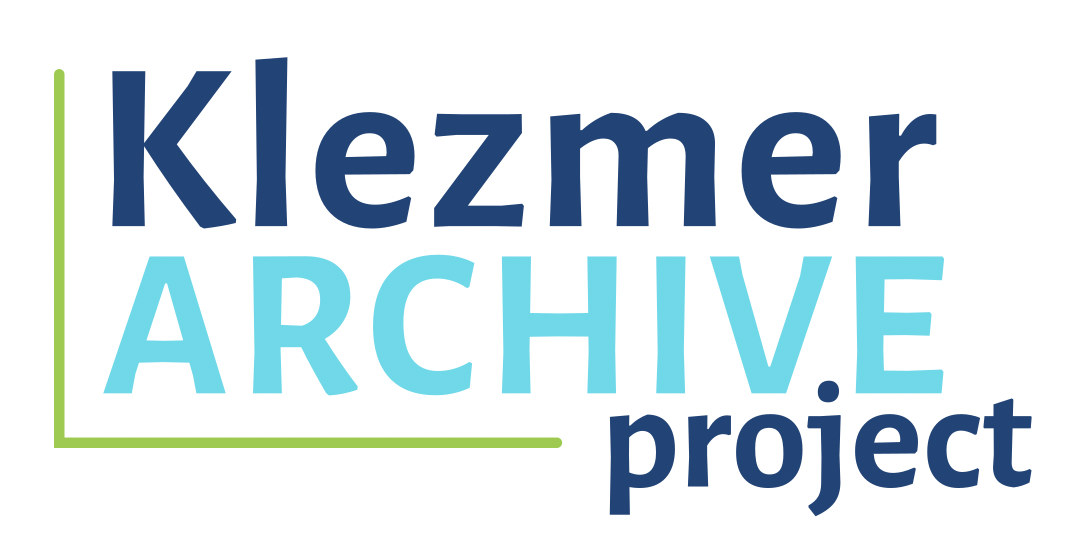

Ah, our beloved “Hannah’s Skotshne” (KMDMP 20-59-1676).

By now, many of you have heard the tale of this tune that has swept around the globe since the launch of the Kiselgof-Makonovetsky Digital Manuscript Project (KMDMP). The original manuscript captured in the photo is torn, folded, and worn to the point of illegibility.

Image 1: Facsimile of the “Hannah’s Skotshne” Manuscript

Nevertheless, KMDMP digitizer extraordinaire Hannah Ochner tackled this piece, providing us with a legible version of the tune from the bits of writing peeking out from the folds and context throughout the tune. When Hannah was done, she submitted her MusicXML file for us to reference as we move into the editorial phase of encoding using MEI.

MEI is an XML specification (similar to MusicXML, which is produced by music notation programs) developed by the Music Encoding Initiative used widely for digitally encoding music in academic and archival projects with similar goals to the Klezmer Archive. The schema is developed in the open and the project leaders welcome changes from the community. Indeed, we have already contributed a few small changes that have been accepted and will be included in future releases. The community also has built a suite of tools that we are excited to use, including the Verovio renderer and MEI-friend editor.

Why MEI? #

MEI allows us to document more details than a typical notation software, including representing ambiguous marks in handwritten scores and supporting editorial annotations. Within a single document we can capture the “manuscript” version (replicates what we see on the page as closely as possible) and an “edited” version (klezmorim-informed, playable version that makes corrections or clarifies ambiguities on the manuscript). This means that rather than printing multiple versions and comparing them measure by measure, we can highlight these differences and the user can choose what version to display depending on their use for the document at the moment! The ability to encode multiple readings of the manuscript (e.g. original, amended/edited, and playable) in a single document allows the MEI file to be the “single source of truth” for the digital notation. MEI encoding not only allows users to render the different readings of the tune for print or screen, it also makes the annotations and editorial notes available to our knowledge graph that will eventually contain the complete record for this item.

In May of 2024, I set out to learn MEI and (foolishly?!?) decided to begin with “Hannah’s Skotshne.” Over the course of the following year, Max Rothman and I had numerous meetings to understand how best to reflect the whole of the tune in a single encoded document. The complexity of “Hannah’s Skotshne” was perfect for exploring the differences between our desired versions, determining what level of detail was necessary vs. too much, and sorting out how to tweak MEI to fit our unique needs. We’re still working on our specific editorial policy (which is informed by our KMDMP Scholarly Editions Policy too!) and many details are unnecessary to relay in full here, but we do want to highlight some of the fun challenges we’ve encountered so far.

Challenge #1: The Key Signature #

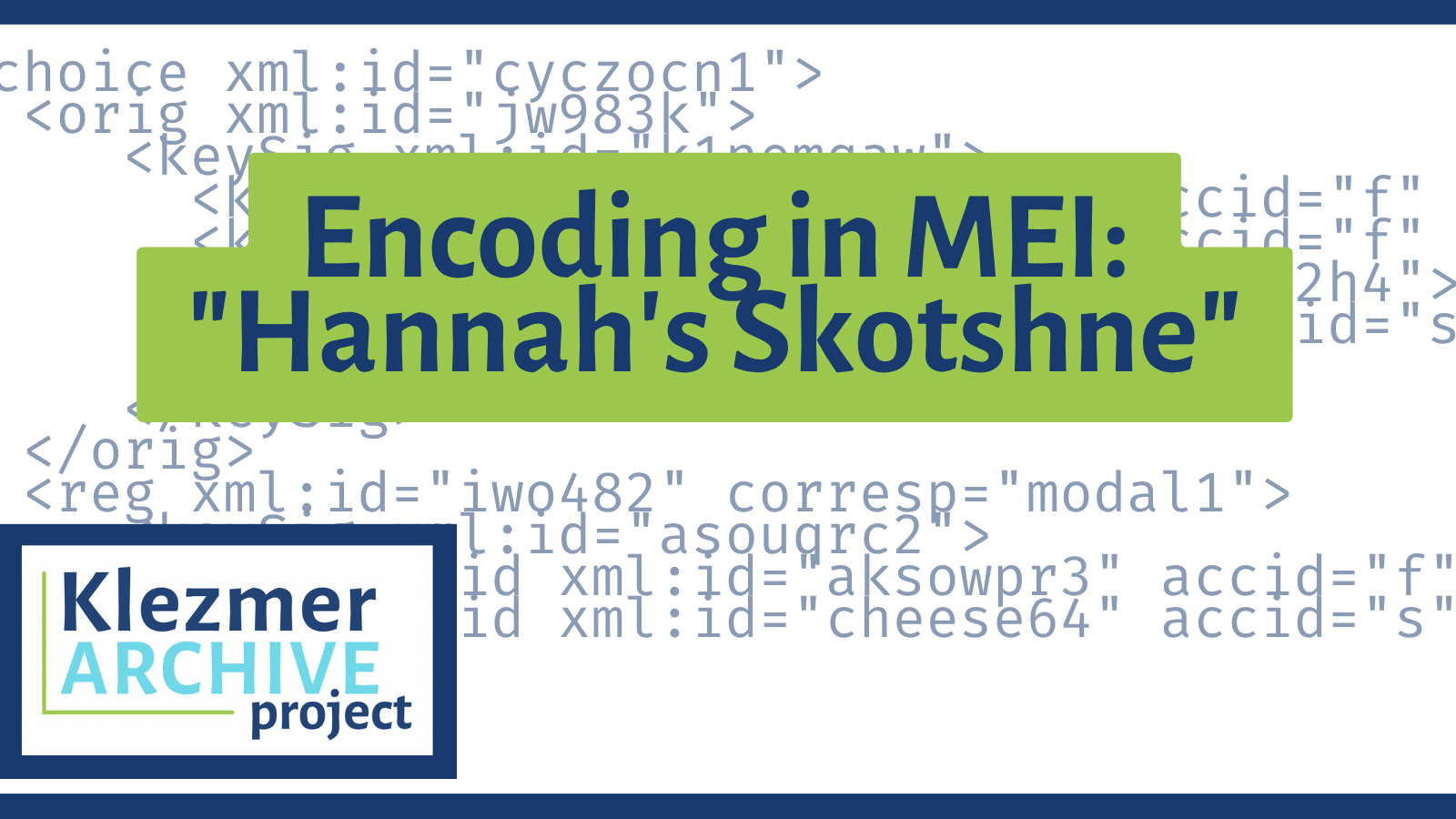

Most notation softwares allow us to create our own key signatures, including the one found on the manuscript with B-flat, E-flat, and C-sharp. What is tricky to document in this instance is the presence of two “hands” that created this key signature and the implications for every instance of the C-sharp throughout the remainder of the code.

The individual who wrote this tune down in the alter klezmer-heft (old klezmer notebook) has written it fully with just a B-flat and E-flat in the key signature, marking the C’s throughout the tune with an accidental. The purple C-sharp matches the writing implement that marks the K-numbers throughout the manuscript, likely Moishe Beregovski, to whom the catalog in Yiddish is attributed.

Image 2: Modal key signature on the “Hannah’s Skotshne” manuscript

In MEI, we can note the original key signature (just the two flats) and the added C-sharp found on the manuscript. In the manuscript version of the tune, the C-sharps throughout the tune will still be displayed as seen on the photo.

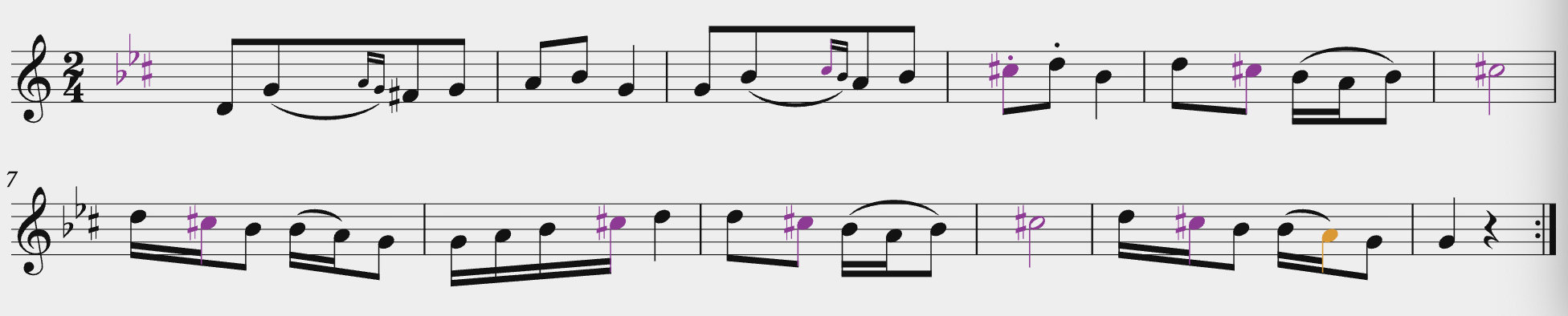

Image 3: Manuscript Version of “Hannah’s Skotshne” rendered via Verovio in the MEI-friend interface.

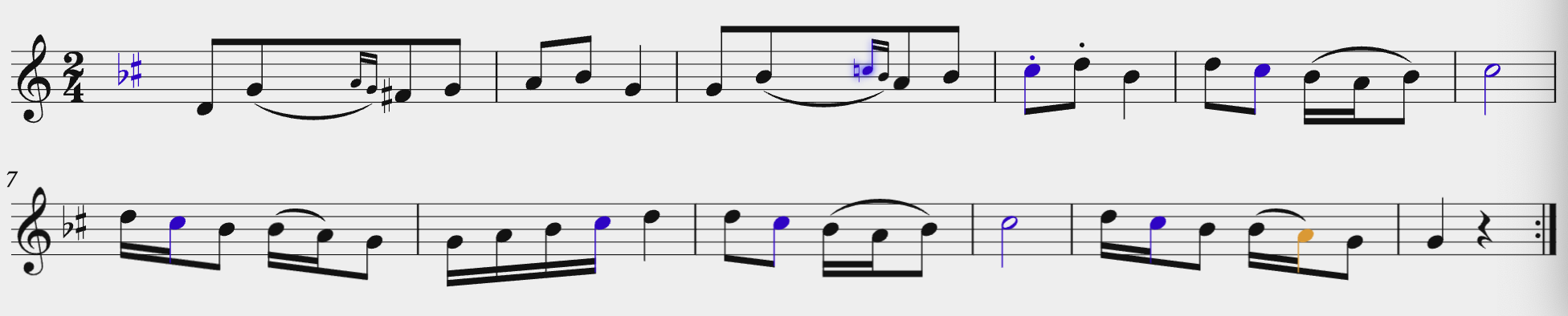

Then, for our edited, playable version in MEI we want to “regularize” this modal key signature for G-misheberakh as found in the Beregovski collection with just the B-flat and C-sharp (no E-flat). The C-sharps in the tune in this edited version will not display the C-sharps or E-naturals, since they are reflected in the key signature.

Image 4: Edited Version of “Hannah’s Skotshne” rendered via Verovio in the MEI-friend interface.

Once we’ve encoded more of the KMDMP corpus in MEI, the future Klezmer Archive website will allow users to view/download both versions of the tune for performance, study, and research.

For those of you interested, here is the current code for the key signature!

<choice xml:id="cyczocn1">

<orig xml:id="jw983k">

<keySig xml:id="k1nemqaw">

<keyAccid xml:id="k10uzq7v" accid="f" pname="b"/>

<keyAccid xml:id="k10gm87c" accid="f" pname="e"/>

<add xml:id="a19bmee" hand="#wud92h4">

<keyAccid xml:id="kp9nu6k" accid="s" pname="c"/>

</add>

</keySig>

</orig>

<reg xml:id="iwo482" corresp="modal1">

<keySig xml:id="asouqrc2">

<keyAccid xml:id="aksowpr3" accid="f" pname="b"/>

<keyAccid xml:id="cheese64" accid="s" pname="c"/>

</keySig>

</reg>

</choice>

Challenge #2: The Grace Note in Measure 3 #

As you can see in the third measure of Images 3 and 4, one C in the original hand that did NOT have a written out sharp next to it - the grace note in measure 3. What do we make of this? Did the original writer forget a C-sharp? Did he intend to leave it a C-natural? Since there is no definite indicator, we leave it as is for the manuscript version and use our best klezmer-informed knowledge to make a decision for the “playable” version. As you can see, we are suggesting that grace note be played as a C-natural and (not visible in the screenshot) have included an annotation to read:

The original key signature of this tune had two flats, but a later hand (presumably Beregovski) added the C-sharp to reflect the klezmer mode of G misheberakh. This note has no accidental in the manuscript. The editors recommend playing this as a C-natural.

Capturing annotations and editorial commentary not only in the general music file, but linked to specific notes, bars, barlines, or other music symbols allows future scholars and musicians to understand our entire editorial process, and encoding the music and annotations together in a single file reduces the likelihood that “text” and “context” become separated in the future.

Challenge #3: Unclear or Obscured Notes/Passages #

The bottom of the original manuscript is, frankly, a mess! Luckily, Hannah provided notes with her thinking about the passages and we can reflect that in the MEI as well.

Let’s take a look at just a single measure, the second to last measure of the tune (ms. 32), for an example of the messiness we are able to document in MEI.

Image 5: Measure 32 in the Manuscript

Image 6: Measure 32 in the Manuscript MEI Version

As you can see, half of measure 32 is completely obscured in the manuscript, but Hannah says “The second half of bar 32 is obscured. Since bars 30, 31 and 33 are identical to bars 9, 10 and 12, it would make sense if 32 was the same as bar 11.” This note is encoded in the MEI for the measure and, as seen above, the “supplied” notes by Hannah are highlighted in orange to show that they were not visible or clear in the original document. When the notes are as ambiguous as in this tune, we have chosen to fill in the missing notes and show an indicator to alert the reader that they are provided by the editors. The MEI-friend editor that we use for our editorial process displays these added notes as orange, but in the future we will most likely use the notational system created by our KMDMP Scholarly Editions team.

<measure xml:id="m18gdncd" n="32">

<staff xml:id="sz7gbai" n="1">

<layer xml:id="l1ygvi2v" n="1">

<beam xml:id="bitg35n">

<note xml:id="n18o2exb" dur="16" dur.ppq="1" oct="5" pname="d" stem.dir="down"/>

<choice xml:id="n17g7u0l" corresp="#modal1">

<orig>

<note xml:id="n172i90l" accid="s" accid.ges="s" breaksec="1" dur="16" dur.ppq="1" oct="5" pname="c" stem.dir="down"/>

</orig>

<reg>

<note xml:id="n172adg0l" accid.ges="s" breaksec="1" dur="16" dur.ppq="1" oct="5" pname="c" stem.dir="down"/>

</reg>

</choice>

<note xml:id="nagf0ud" accid.ges="f" dur="8" dur.ppq="2" oct="4" pname="b" stem.dir="down"/>

</beam>

<beam xml:id="bd6r2vn">

<supplied xml:id="sslvljs2" reason="paper_fold" extent="total">

<note xml:id="nipvbxc" accid.ges="f" dur="16" dur.ppq="1" oct="4" pname="b" stem.dir="down"/>

<note xml:id="n690ue4" breaksec="1" dur="16" dur.ppq="1" oct="4" pname="a" stem.dir="down"/>

<note xml:id="n17cwjkj" dur="8" dur.ppq="2" oct="4" pname="g" stem.dir="down"/>

</supplied>

</beam>

<annot plist="#sslvljs2" type="reason">The second half of bar 32 is obscured. Since <annot plist="#mgh3z2p #m31ivoo #m1u0xqe0" type="ref">bars 30, 31 and 33 </annot> are identical to <annot plist="#mohjwj #m1lipan0 #m1pzhz6f" type="ref">bars 9, 10 and 12</annot>, it would make sense if 32 was the same as <annot plist="#m1m8hdny" type="ref">bar11</annot>.</annot>

</layer>

</staff>

<slur xml:id="s1w109e0" endid="#n17g7u0l" startid="#n18o2exb"/>

<slur xml:id="sukmd9f" endid="#n690ue4" startid="#nipvbxc"/>

</measure>

There are thousands of tunes! What happens next? #

As of this writing (May 2025) Clara and Max are in the process of writing out the explicit choices that we’re making in the coding (Ex: Do I code accidentals as “elements” or “attributes”?). Max has already built automatic checks that will help future editors produce consistent encodings. We’re working with Christina soon to create a collaborative workspace for documenting what tunes are pre-processed and converted into MEI, edited, first-pass complete, validated, polished up, and finished. After we complete a bunch more test tunes (coming up soon is a liturgical piece without barlines!), we’ll be bringing other team members into the process and working through the rest of the KMDMP tunes.

You may be thinking, if “Hannah’s Skotshne” took you a whole year, will this EVER BE DONE?! Fair question, but we can safely say “yes!” We definitely dug into the hardest one first, had to develop strategies and parameters, read a bunch of guidelines, and…well… I had to learn how to “code”! We’re on our way and look forward to sharing more as we go!