When considering how to accurately structure the dataset of klezmer music, we must answer a surprisingly complex question: how do we define a tune? And how do we best capture our diverse and often conflicting understandings of tunes into a clean, consistent data model?

The classic Y.L. Peretz short story “A gilgul fun a nign” tells the tale of a nign as it migrates from town to town, starting off as a Hasidic wedding melody, moving to the Yiddish theater, a circus, back to the Hasidic rebbe, and finally off to America. Though the essence of the tune remains constant, the performance style and social context are continuously transformed. Is the tune from the beginning of the story the same at the end? Or does it become something new at each stage?

In something like Western classical music, a piece of music originates with a titled score that is attributed to a particular composer. Perhaps there are later edits to the score, rearrangements for different ensembles, even mashups with other pieces or genres. Stylistic performance preferences for the piece may vary over time. All these variations, however, can be cleanly associated with the original named entity.

But in klezmer, along with many other folk music traditions, the concept of a tune is not quite so clear cut. The inconsistencies we encounter include:

- Naming: Klezmer tunes were largely unnamed until the early 20th century, when they started being recorded. Today, many tunes are still named after their dance style and/or place of origin, and multiple different tunes may share the same name (like Odessa Bulgar.)

- Co-territorial variants: Many klezmer tunes have relatives amongst non-Jewish music from the same regions. These pairings may appear nearly identical notewise in transcriptions, yet performance and recordings reveal the often nontrivial differences in style and interpretation.

- Shared sections: Certain common motifs, and even entire sections, appear across multiple tunes. Additionally, ensembles may assemble their own new tunes from a Frankensteinian selection of existing tunes.

- Reinterpretation: The same note sequence may be played with different accompaniment or in a different dance style and become something completely new.

For these and other considerations, we must ask: are these the same or different tunes? When and how can we determine whether multiple transcriptions or performances are the “same tune”? Within the Klezmer Archive team, we’ve named this the “fuzzy tune boundaries” problem, loosely rooted in the concept of “fuzzy logic” in computer science.

The short answer to the above questions is that we can’t, and shouldn’t, attempt to prescriptively say what is or isn’t the same tune. Our models must attempt to capture, rather than reduce, the vagueness implicit in this data.

Furthermore, the complexity of this data is exactly what’s exciting about it. Each “tune” tells a unique story that we can piece together from the transcriptions, recordings, writings, and other data sources associated with the tune.

So, where do we go from here?

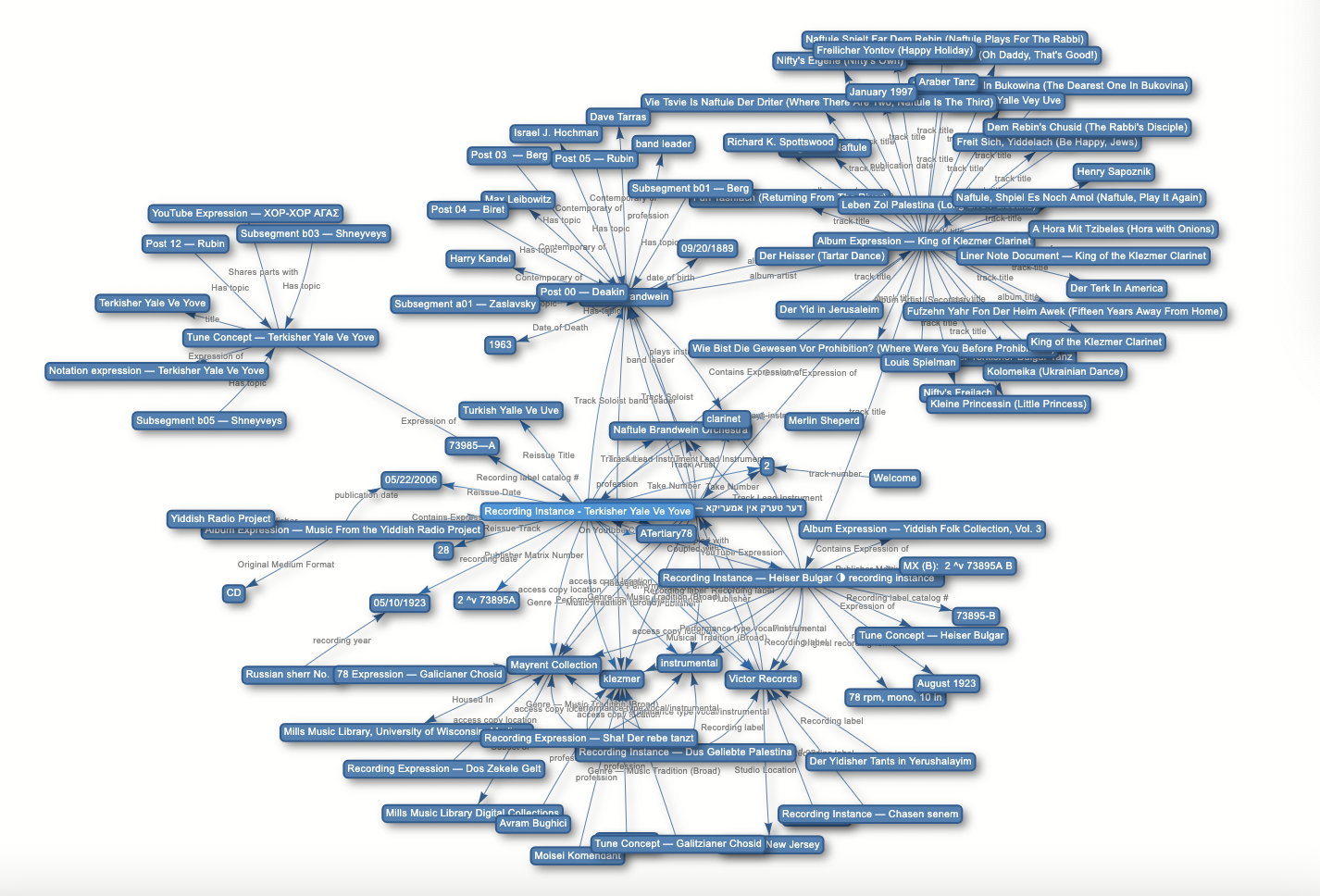

We plan to store our data as a knowledge graph — a network consisting of real-world entities (“nodes”) and the relationships between them (“edges”). This post will stay fairly high-level and mostly non-technical, but we’ll be sharing more on the specific capabilities and implementation of knowledge graphs in future blog posts.

Figure 1: An example graph from our team’s experiments with The Networker (https://www.infoloom.com/)

We can define a “tune artifact” as any input to our system, represented as a single node in our graph. An artifact can be a specific transcription, a recording, or any other type of data that relates to a specific instance of a tune. At this level, it’s important to distinguish that a tune artifact is not equivalent to a tune.

Then, we can begin to define all the ways in which tune artifacts relate to each other, which become the edges of our graph. These relationships fall into some broad categories, namely performance/dance function, musicological function, and social function. Specific edge relationships can include: genre; performances of a tune artifact (e.g. a recording of a specific Beregovski tune); performance notes; medleys; albums; and derived melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic similarities. For certain relationships, an “edge weight” (a number attached to an edge) can represent how closely related two tune artifacts are. For example, we might define a function that calculates how similar a pair of transcriptions is and assigns a number in the range 0 to 1 to reflect completely different to completely identical note sequences.

Finally, we can analyze our graph to find closely connected clusters of tune artifacts. We might call a cluster a “tune family”, as proposed in the paper “Towards Integration of Music Information Retrieval and Folk Song Research”: “The melodies and the texts [of folk songs] are learned by imitation and participation rather than from books. In the course of this oral transmission, changes occur to the melodies. The resulting set of variants of a song forms a so-called ‘tune family’.”

Just as a tune artifact does not equal a tune, so too does a tune family not exactly equal a tune — though a tune family is functionally closer to what we’d casually call a “tune.” While these semantic distinctions may sound pedantic, recognizing these differences has led to further experimentation and research into ontological concepts.

In this early stage of researching and beginning to design the architecture of the Klezmer Archive, we are fortunate to have members of our team with expertise in both library sciences and computer science, as well as deep musical knowledge across the entire team. Discussions like that of Fuzzy Tune Boundaries emerge from this juxtaposition of methodologies.

Please check back for more upcoming posts, join the Klezmer Institute email list to receive updates, and be in touch if you have thoughts or questions to share with the Klezmer Archive team!